Britains Detroit.

The modern towns and cities of Britain were built on industry. And some became famous the world over for their role in one industry in particular: Sheffield for steel, Manchester for cotton.

Yet another northern city’s pivotal role in a global trade hasn’t entered the public consciousness in the same way. And as it battles to leave behind the worst side-effects of deindustrialisation, it’s a city with an image problem.

This is the story of Bradford.

The foundations

Wool is one of the bedrocks of Britain's wealth. Once so important to our economy, in fact, the speaker of the House of Lords sits on a wool-stuffed seat known as 'the Woolsack'. This seat was previously occupied by the Lord Chancellor, the highest-ranking office of state.

The wool industry’s legacy persists to this day; the UK has more sheep breeds than any other country in the world – over 60 – in a flock of 22 million, tended to by more than 40,000 farmers.

Historically, when wool cloth-making was a cottage industry, it was concentrated in East Anglia. But with industrialisation, processing was concentrated in Yorkshire – courtesy of abundant cheap coal, soft water, and fast-flowing rivers. The perfect conditions for mills.

Of the 224,514 jobs the wool industry provided, 187,204 were in the West Riding of Yorkshire. Leeds became known for woollen – the bouncy, light, full-of-air sort of wool used to make knitwear. And Bradford became known for worsted – the high-quality processed wool cloth used to make tailored suits and jackets.

By 1841 there were 38 worsted mills in Bradford town and 70 in the borough. It was estimated that two-thirds of the country's wool production was processed in Bradford.

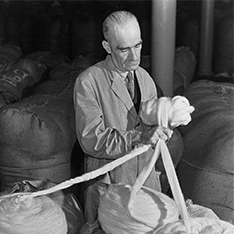

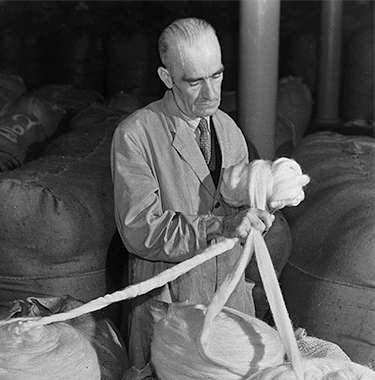

Worsted is made from the longest wool fibres from across the stomach of the sheep. These long fibres are twisted, making the wool not only fine but very durable.

In order to make worsted, raw wool is washed and combed, to remove short fibres. The resulting, semi-processed material is called top. Creating top by hand produces about 20lbs a week – but the introduction of combing machines increased production to about 200lb in a single, 10-hour working day.

Processed wool tops are then spun to create yarn, and woven into cloth. But before they can be spun, tops must have oil and water added as lubricant. And with the growing market for wool top – sold by weight – there was a need to set standards for moisture and oil content, because unscrupulous traders would add excess water to make them appear heavier.

If you’re going to set standards, you have to test for them. And Bradford’s Conditioning House is where that testing would take place.

Conditioning House

Conditioning House and its fortunes over the last century-or-so hold up a mirror to Bradford itself.

Established through an Act of Parliament in 1887, Conditioning House was purpose-built and completed in 1902 and was the only one of its kind in the country. A certificate from Conditioning House was as good as a bank note anywhere; if Bradford's testers said it was good, there was no arguing.

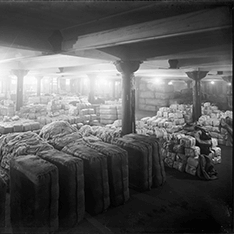

At one point, almost 70% of all wool produced in the UK was brought on-site for quality-checking, much by barge – in addition to huge quantities of wool imported from around the British Empire, notably Australia.

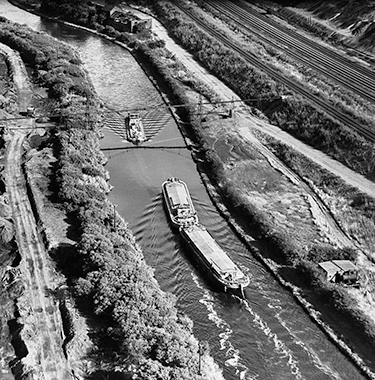

Its four imposing storeys face Canal Road (also known as the A650), which runs alongside the route of the Bradford Canal, long since filled in. Bradford was something of a backwater until the canal arrived in 1774; a 3.5-mile spur of the Liverpool-Leeds canal ran into Bradford from Shipley.

At first, the canal was used to ship iron and coal to the coast for export. In time, it was used to bring in wool for processing, then to export finished cloth.

Conditioning House was just one cog in the machine that was Industrial Revolution-era Bradford. In 1902, over 300 mills were producing worsted in the city, and the industry employed tens of thousands – many of whom lived in poverty, while working long hours in unpleasant conditions. The ideal environment for wool processing is cool and damp – the kind of conditions in which common diseases thrived.

Image provided by Bradford Museums & Galleries

Conditioning House and its fortunes over the last century-or-so hold up a mirror to Bradford itself.

'Woolsorters' disease', also known as 'La maladie de Bradford', affected those processing exotic wools imported from around the world. Alpaca and mohair, it was later discovered, carried microscopic anthrax spores. Many wool workers died before Dr Friedrich Eurich, a bacteriologist employed by the council in a laboratory at Bradford Technical College, led research into developing methods for disinfecting wool.

Those fortunate few who didn’t live in poverty weren’t far away. Grand Victorian villas lined the streets of Manningham – a once-desirable area popular with the middle and merchant classes, and just north of Conditioning House.

Wool industrialists were celebrated for bringing prosperity to the city. And their impact on the area lingers on - parts of Bradford are named in their honour: Lister Park after Samuel Lister; Saltaire (a model village and UNESCO World Heritage Site) after Sir Titus Salt.

The wool industry was the backbone of Bradford’s entire economy. It even made the local sewage works profitable.

There was so much lanolin in the local water supply that they had to develop a process to remove it, by heating the sewage.

Lanolin was sold and used in lipsticks, soaps, and as industrial grease on big old locomotives – superceding the canals in transporting wool to and from Conditioning House.

Wartime

In October 1939, the wool industry was given the task of making greatcoats for the Second World War army, numbers equal to 25 years' supply under normal conditions.

Bradford’s war effort doubtlessly helped to save lives and reduce suffering.

Wool was chosen for military uniforms as it’s more flame-resistant than cotton and doesn't melt like acrylic or other manmade fibres – which could leave soldiers with painful burns.

Lister & Co produced more than 10,000 miles of military fabric and cord, produced with only half the normal workforce.

Bradford’s war effort doubtlessly helped to save lives and reduce suffering.

Despite this, the war was not good for business. Poverty, the requisition of factories, and the ‘make do and mend’ initiative all had a negative impact on domestic demand for wool cloth.

Deterioration

The fierce fighting of the war led to technological advancements that had applications far beyond the front line. New technologies meant it was easier and more efficient to test samples from wool bales on farmers’ premises, rather than transporting them to Bradford for testing.

Conditioning House’s role began a long, slow decline.

Simultaneously, the spinning mills also deteriorated. A more efficient combing technology was developed on the continent, making the system used in Britain uncompetitive.

Mill owners hoping to use this new technology struggled to modernise many of Bradford’s multi-storey mills to accommodate the modern machinery; floors would’ve needed strengthening to cope with the additional weight and vibration. Plus, with this machinery much more productive, only a fraction of the space and workforce would be required.

Fashions evolved. Changing consumer preferences led to growing demand for casualwear. Traditional cardigans, suits and heavy coats came to be seen as stuffy, old-fashioned and excessively formal.

Retailers demanded new (and, importantly, affordable) styles; British manufacturers struggled to compete against cheap labour from Asia, which used new fabrics like rayon (a heavily-processed material made from tree pulp) for suits, and ever-more sophisticated acrylics for sweaters. It was the perfect storm. One Bradford could not weather.

Despite its challenges, Bradford remains the modern epicentre of Britain’s wool industry. The British Wool Marketing Board was established in 1950 and is still based on Canal Road.

It operates a network of wool grading depots around the country, and an auction house in Bradford where graded wool lots (of similar type, quality and characteristics) from different farms around the UK are combined and sold to registered buyers – electronically, of course.

The lots are then shipped to processing facilities. There, an intensive cleaning process called scouring takes place. This is where the impact of globalisation becomes stark.

Lower labour costs and different environmental regulations have resulted in a significant shift in this primary processing towards China.

Some British-grown wool leaves for the Far East, is processed, and is then shipped back as yarn.

Only two commercial scouring facilities are still operating in the UK - both are in Bradford.

Demolition

In Britain, globalisation contributed towards a reduction in manufacturing jobs of over 60% between 1979 and the early 2000s.

In the textiles and apparel industry, it was closer to 90%.

The decimation of Bradford’s textile industry has had long-lasting effects. Rates of unemployment and deprivation are persistently high; in a 1996 survey, half of Pakistani and Bangladeshi households had nobody in full-time employment. In 2001, tensions flared into the Bradford Riots. At that time, 35% of Bradford's adult population lacked any qualifications.

A YouGov poll of public perceptions named Bradford the most dangerous of Britain's 10 most populous cities. Statistically, it's the second safest.

By 2010, the gap between the most and least deprived areas was the largest in the country. Manningham, with its streets of villas, is now among the top 5% most deprived areas of the country – 35% of households have a total income of under £15,000. Many of these grand old homes have been divided into flats and bedsits.

Old stereotypes about poverty and criminality linger on. A YouGov poll of public perceptions named Bradford the most dangerous of Britain's 10 most populous cities. Statistically, Bradford is now the second safest, behind Sheffield.

Conservation

With its poor reputation, you might not expect the centre of Bradford to be so grand. But the rapid rise of the textile industry in the 19th century packed Bradford with gorgeous gothic revival architecture. Its equally rapid decline in the 20th century meant that the local council lacked the money for ‘utopian’ redevelopment schemes that flattened many similar cities it in the name of ‘progress’.

So, in the noughties Bradford was one of the best-preserved Victorian cities in Britain. That said, many buildings were unloved and unused, presenting unique opportunities for ambitious investors.

Conditioning House itself was abandoned and sold by the council; the original buyer had plans to turn it into a hotel and conference centre. A subsequent plan would have seen it become a commercial office. It’s changed hands multiple times since, with no owner being able to execute their plans.

Grand ambitions in the mid-2000s would have seen the reinstatement of the canal, seeing Conditioning House developed as waterside apartments. That scheme was cancelled after the last global financial crisis.

That ambition speaks of the efforts being made by local leaders to change Bradford’s public image. In 2008, the city bid to become the European Capital of Culture – it's been demonstrated that winning can serve as a catalyst for the transformation of a city. It lost to Liverpool.

Nevertheless, there's been over £1bn in investment in the city centre since 2010.

Investment in the city centre at this time was in stark contrast to post-war public policy, which indirectly encouraged car ownership. Leafy, spread-out suburbs were built to replace sooty, smoke-filled terraced streets, while motorways were invested rather than railways. Those grimy inner cities were abandoned by any who could afford to leave, and car ownership became a status symbol.

In the 1990s, 80% of people were driving by age 30. But now that 80% milestone is reached only by age 45. Men under 30 are driving half the miles their fathers did, and there’s been a 20% reduction in commuter trips per week since the mid-90s.

Millennials fell out of love with motoring, and the car revolution switched to reverse.

Whether it’s the cost of fuel, insurance and parking, environmental concerns, or the technological revolution requiring less travel, fewer young people were deciding that running a car was worthwhile.

Between 2002 and 2015, Bradford’s city centre population increased by 146% (from 1,300 to 3,200). But it pales in comparison to nearby Leeds (city centre population: 32,300) and similarly-sized Bristol and Nottingham (both over 30,000 each).

Bradford was gradually becoming the perfect hub for businesses looking for a central location, but wishing to take advantage of the growing remote working culture and shift from the UK’s most populous cities.

Fighting back

Bradford has some catching up to do. The once-prosperous Motor City is similarly down-at-heel as a result of deindustrialisation and globalisation. But much like Detroit, Bradford is being celebrated as a city of expression, pride and diversity. Now Whole Foods is setting up shop in Detroit, and Google and and Microsoft are opening offices.

Bradford was named ‘most improved’ city to live and work in by PwC in 2019, highlighting jobs and work-life balance in particular.

Today, Bradford is competing against Luton, Chelmsford, Southampton and others to become the UK’s City of Culture for 2025.

Campaigners are hoping Bradford’s bid holds an ace up its sleeve: 2025 will mark 200 years since the last Blaise Wool Festival in the city; the little-known St. Blaise is the patron saint of Bradford, and was martyred with a woolcomb.

Perhaps Bradford’s most famous creatives are artist David Hockney, and the playwright/novelist J.B. Priestley, who penned An Inspector Calls. Today, the Priestley name remains prominent in the city, having also been the name of two former Bradford mayors. Priestley Street is about 200 metres from Conditioning House, while Priestley Homes is helping propel Bradford’s renaissance.

By 2019, Bradford was being named most improved city to live and work in by PwC, with jobs and work-life balance highlighted.

Priestley Homes recognised the huge potential in both Bradford and Conditioning House, acquiring the building in 2017. The business has invested millions in regenerating it, including £8.5m of development finance from Together. Nathan Priestley, the man behind the scheme, remembers Conditioning House in more prosperous times: his grandfather worked there as a driver.

"It's a unique building that had a great deal of potential after standing neglected for 30 years."

"Working with listed buildings can be a challenge, but the result of the restoration of this historic site is a great achievement. We believe Conditioning House sets the standard for other residential developments in Bradford, showcasing the scale of transformation that can be achieved when breathing new life into our heritage buildings."

Nathan Priestley, CEO of Priestley Homes

Conditioning House’s rebirth is emblematic of Bradford’s fight back against deindustrialisation. As we embark on a new path as 'Global Britain', it’s a city with all the ingredients to succeed.

The population is growing twice as fast as the national average, and it’s the youngest city in the country (23.7% of residents are under 16). Ethnic minorities make up 36% of the population, and over 150 languages are spoken by children in Bradford schools.

As the country forges a new role for itself, we should perhaps consider if Britain will become a bit like Savile Row: a relatively minor manufacturer in terms of volume, but known around the globe for the quality of our product.

Want to get in touch?

We look at your individual situation, not just your credit score, and get to know the bigger picture. That's common sense. And more of us have less-than-perfect credit. But many of us have the same hopes and aspirations as always. And we know this, because we share them with you.

Get in touch